Learning to Write: Is it necessary and does technology support or inhibit the process?

Dr Maria Kay

a.maria.kay@btinternet.com

ORCID 0009-0001-6445-0647

Abstract

The process of learning to write is complex and as cursive writing is in decline and the possibility of online exams looms closer, one is led to question whether there is a need to learn to write by hand. Investigated here is research which determines the difference between writing by hand and writing using a keyboard in terms of learning and utility. Whilst it is often considered that the formal process of learning to write begins with the learning of letters, there is an informal building of foundations which supports the success of this process. It is possible that the physical process of handwriting itself contributes to writing and learning in a multiplicity of ways that keyboarding cannot.

Keywords: handwriting, typewriting, keyboarding, early literacy

No conflicts of interest are applicable to this article

Introduction

In this day and age of technical devices – smartphones, tablets and laptops, it seems that there may be little need for writing onto paper. Even when a person does not wish to type text, they may use speech texting where their spoken words are instantly converted to text, ready for transfer. The digital voice recorders of today produce instant print and although they may struggle with accent, they are becoming increasingly adept at recognising homophones such as ‘write and right’ and supplying correct spellings. The skill of organising thoughts so that they are presented in a coherent and meaningful way can even be undertaken by AI, which may lead some to wonder whether pen and paper are becoming tools of the past (Trubek, 2016) and headlines such as ‘Writing’s on the wall for the humble pen and pencil’, Samuel, (2023) in The Times newspaper, suggested the same. A survey in the UK by Docmail, found that 41% of two thousand adults surveyed had not written more than a grocery list in the previous six weeks (Medwell and Wray, 2017).

However, for those who enjoy handwriting, there is pleasure to be had from the feel of pen on paper, the smell of a writing book and the inky pen, and the physical formation of each letter with its individual swirls and curls that cannot be enjoyed by the mere tapping of keys on a machine. Handwriting also allows the writer to doodle and twiddle a pen, actions not dissimilar to the use of stress balls, to help to focus the mind on the task in hand and may possibly foster creativity in a way that using a machine does not.

The Importance of Handwriting

In a school setting, children are required to learn to handwrite (although the requirement for cursive (joined up) writing has been removed from the CCS curriculum in the USA) and to submit handwritten work for classwork, assessments and most external exams. Currently, a child’s output at school is measured in terms of their handwritten submissions. Inability to write by hand may cause difficulty with meeting production deadlines and have a very negative impact upon school life, academic progress and ultimately an individual’s self-esteem and future life prospects.

It is possible however, that handwritten submissions may not always be the requirement. Coombe, (for Ofqual, 2020), investigated barriers to the adoption of online assessment: IT provision, implementation and maintenance of equity and considered that computer-based assessments for schools, seems to be an inevitable next step. Whether handwritten or typewritten, assessment is generally in written format.

In his book ‘The Myth of Laziness’, Levine (2003) finds that many students who are labelled as lazy, in fact have problems with handwritten output. He explores the importance of handwriting as a method of output and suggests that it impacts not only a person’s school life but that it can affect the rest of life too. He suggests that handwriting requires the co-ordination and integration of many neurodevelopmental functions and academic subskills. Levine proposes that writing by any medium requires a student to generate ideas, organise thoughts, encode ideas into clear language, identify letters (letter formation, if by hand, or matching if by keyboard), match language sounds to symbols, match visual and auditory patterns, remember unique spellings, remember rules of punctuation, recall facts for what is being written, possess effective hand-eye co-ordination, plan and monitor work, apply concentration, mental effort, focus and energy and that these must be integrated and synchronised. Explored in this article, is the idea that maybe the physical process of handwriting in some way facilitates the enactment of this vast array of skills in a way that typewritten production is not able to do.

Despite the importance of being able to produce written output, there are over a fifth of students leaving school with inadequate writing skills in America and nearly a quarter of UK students in the same predicament. For grade 4 and 12 respectively only 86% and 79% of students achieved at or above the basic writing levels in the National Assessment of Educational Progress (The Nation’s Report Card, 2020) in the USA and in the UK only 75.5% of pupils reached the expected standards in 2019 (Department for Education, 2019).

Learning to Write

Before children are taught to write in a formal setting, some children being to engage in their own early attempts at writing, referred to as ‘mark making’ (Dunst and Gorman, 2009; Friedrich et al, 2021). Children learn that print has meaning and is a form of code, through experience of literacy practices, being read to, being able to hold and look through books, seeing environmental print and having attention drawn to its meaning and observing others engaged in the processes of reading and writing. As a result of seeing others write, they may wish to create their own meaning from text. A child’s early attempts at writing may often look like lines of circles or squiggles, this shows that the child has learnt that text is linear and composed of symbols which represent language. It is possible that this practice is declining due to the more likely scenario that children are observing parents keying in text to devices rather than observing parents engaging in handwriting.

Most children will learn to read letters before they begin to write them and thus will have some familiarity with the letter shapes. However, in Montessori settings, children learn to write before they learn to read; an idea also advocated by Chomsky (1971) who proposed that this allows children to be active participants in their own learning. A hands-on approach is used in Montessori, which requires motor, cognitive and visual skills; children are shown how to trace sandpaper letters in the correct direction and taught the letter sounds. It is proposed as a more natural process which offers an excellent foundation for reading. The physical movement is remembered by the brain as well as the visual imprint, this is termed ‘muscle memory’; thus, the visual and auditory memory are also engaged, such that when children are given a writing implement, they will already know how to form the letters. To deprive children of this aspect of writing would seem to be a retrograde step. Learning to write is a complex process requiring the convergence of many skills and knowledge of text as identified below:

- Knowledge Required Children must be aware of concepts of print: the purpose of text; book and print orientation; the purpose of letters, words and sentences; punctuation and the alphabetic principle (the understanding that letters represent language sounds), also, the understanding that print is a visual form of spoken language. Simply learning to name and reproduce letters does not teach children to write. Learning to read and write, unlike spoken language is not innate and must be systematically and explicitly taught.

- Language Skills Children must possess effective spoken language skills to subsequently produce it in written format. Roessingh, (2018:22-23) states that ‘A robust vocabulary knowledge is the decisive factor in successful transitioning from early to academic literacy…’ and productive (spoken) language is predicated upon receptive language (what is understood). Research by Barus and Panjaitan (2022), also showed that an extensive and rich vocabulary has a significant correlation with writing skills. Children with weak oral language skills lag behind their peers in terms of their writing related skills (Puranik and Lonigan, 2012) and Cowie et al., (2002) showed that prosodic awareness (the awareness of stress patterns within words) plays an important role in the acquisition of both reading and writing.

- Phonological Awareness In order to learn to write and to spell children need to have phonological awareness, an awareness of the sound units in language at the syllabic, onset and rime and phonemic levels. It has been established that phonological awareness is the undisputed major predictor of literacy success with phonemic awareness being the strongest predictor of the three levels of syllable, rhyme and phoneme (Martin et al., 2024). A lack of phonological awareness can lead to problems with encoding letters and words to print. Roessingh proposes (2018:24) that ‘words must be encountered hundreds of times for youngsters to notice, understand, segment, and manipulate the sounds to form words, and then to make the systematic connection between phonemes in spoken words and the letters used to represent them in print.’ Thus, determining that practise in the writing of letters will support retention.

- Physical Skills The production of a handwritten alphabetic character requires muscular and skeletal strength and maturity in the hand and body to manipulate a writing implement, proprioception, the sense of where the body is in relation to other objects and body parts to each other, the ability to make the pencil touch the paper at the correct starting point and flow in the right direction and complete it at the given point, the necessary control to form the letter of the correct size and in the correct place, bi-lateral co-ordination, the use of one hand to write and the other to steady the paper and the ability to sequence writing movements at a regular and consistent pace.

- Cognitive Skills It is necessary to engage visual memory to remember the 48 shapes of the letters of the Roman alphabet (c, o, p, s, u, v, x and z are the same in upper case but larger). The auditory memory is required to learn the language sounds represented by each alphabetic character or string of characters and the sequence they must follow. In order to express ideas effectively in a written format it is important to understand how written text differs from spoken language and how it is to be presented. A study by Puranik and Lonigan (2012), they found that a child’s cognitive ability impacted emergent literacy skills.

- Visual Skills The ability to recognise differences in shape and direction of written letters is required, the ability to track text with eyes working together, the ability to process what is viewed, accurately and peripheral vision, being able to see a letter or word within other words or letters, being able to focus on letters within words and words within paragraphs are required.

- Sound to Symbol Correspondence and Beginning to Write Ultimately children must learn to match language sounds to their corresponding alphabetic representations. This is the usual point at which formal literacy teaching begins and which much attention is given as to how children should be taught.

It is at the point when children begin to learn about the alphabet that they will begin to write the letters. Although children may be exposed to letters on a screen and may have an interactive screen to learn to match letters and sounds, it is unlikely that their first writing experience will be screen based. A young learner will not be taught to write by typing, although they could well be given a digital pen to use on a screen.

It should be noted that in typewritten text some letters appear different to the form children will initially learn, for example the letter ‘a’. A child will never be taught to write an ‘a’ in this form. They will be taught to write one like this: ‘a’ and most texts for beginning readers have this form. The typewritten ‘g’ is also anomalous with the handwritten format.

If these skills are compared to simply depressing a key on a keyboard, then it seems that physically producing letters appears to be an arduous task for a young child. It becomes clear also that the task of handwriting activates more areas in the brain than typing; this was confirmed by James and Engelhardt (2012). The extent to which this brain activity supports literacy learning may be a major reason that the physical activity required of handwriting is superior to that of typewriting.

The Relationship between Reading and Writing

According to Ehri (2000) reading and spelling develop in a mutually dependent way; each supports the other. Kim (2022) in her abstract, describes this reciprocal relationship in the ‘interactive dynamic literacy model’ thus: ‘reading and writing are part of communicative acts that draw on largely shared processes as well as unique processes and skills’. Ehri (1997) identifies the sharing of knowledge sources: memory, alphabetic system and knowledge of spellings, as being the same in reading and spelling. It is therefore surprising that reading and writing are mostly taught separately as observed by Moran and Billen, (2014). They suggest that reading and writing should be taught together, and that the connection should be made explicit and taught in meaningful contexts.

Orthographic Mapping

The ability to confidently and correctly write and spell a word occurs as a result of a process identified by Ehri (in Kilpatrick, 2016) and referred to as orthographic mapping, the embedding of correct spellings in the brain. For orthographic mapping to take place, a person must know the meaning of a word, its pronunciation and the visual representation of the sounds within the word in the correct order, which make up its unique form. If a child can spell words correctly then they can automatically read them as they are embedded in the brain. Knowledge of spelling facilitates the processes of both reading and writing. Knowledge of the grapheme-phoneme relationship to sound out novel words when reading and learning their meanings, activates orthographic mapping and helps children to improve their vocabulary (Ehri, 2014).

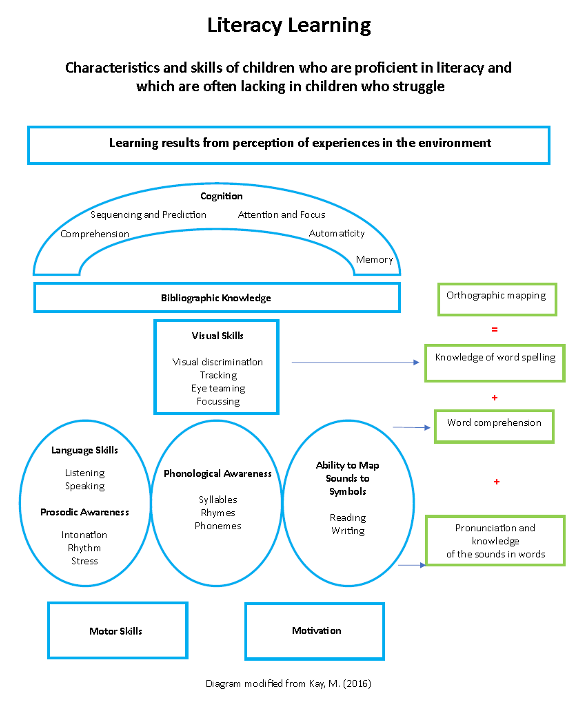

The diagram below summarises the skills possessed by those proficient at literacy, which are assimilated from a person’s environment through their perception of their experiences and illustrates how these skills and experiences support the process of orthographic mapping.

Keyboarding

The skill of learning to use a keyboard is one that children are required to learn today. The keyboard is likely to be familiar to most children. They may observe it being used by others and it may be encountered for input to tablets and phones even by preschool children. The necessity to touch-type may not be vital to speed and accuracy. According to Dhakal et al., (2018) some people are able to type as quickly and as accurately with random fingering, as those taught to touch-type.

However, if learning letter formation is supported by the physical process of handwriting how can this be accomplished by the depression of a key when each physical depression is the same? The skills required on a keyboard are those of letter memorisation and depression of a key in the correct location. There is research evidence from Spilling et al., (abstract, 2022) to support this method of teaching letters as an option. They state that to date there is ‘no clear evidence to support choosing handwriting over keyboarding or vice versa as the modality children should use when they first learn to write’ and their own research confirmed this.

Spilling et al., (2022) suggested reasons for using typing over handwriting such as, that children are able to see that the letters they are producing are the same as they look in books; although it needs to be considered that the letters on a keyboard are in upper case and this may add to the difficulty of location as children must know the relationship between the upper and lower case characters before they can use a keyboard. Spilling et al. also proposed that the selection of keyboard letters is less cognitively demanding and motorically easier than physically forming the letters, although again it could be argued that a child must already know the letter, transcript the image to upper case and then locate it on the keyboard; this could initially be much slower than handwriting. Certainly, a key depression is faster than the formation of handwritten letters, The keyboard also offers the opportunity for real-time feedback in the form a spell-checker. Although this may be useful for older children, it is unlikely to be useful for those learning letters. Spilling et al. also suggested that the availability of the keyboard offers a visual cue for the letters, children only have to choose one; relying only on recognition and not retrieval and production.

There is no doubt that once children are able to write, the use of a keyboard is a faster input medium than handwriting. Particularly for children who struggle with the physical writing process, the keyboard may offer a useful alternative to handwriting (Conway and Amberson, 2004). For such children, whilst battling with letter formation, there is less free cognitive capacity for expressive thought; if a student can benefit from some relief in this area, then this offers a compelling argument for the use of a keyboard as a method of output production.

Conversely however, Berninger et al., (2009) in their study, found that children with and without learning disabilities were able to write faster and produce longer pieces of work by hand than by keyboarding. In terms of quality of writing, Connelly et al. (2007) found no evidence of better performance when handwriting over keyboard input, whilst Berninger et al., (2009) found that fourth and sixth graders wrote more complete sentences by hand. It is possible that keyboarding may suit some students more than others and that successful use is due to familiarity and practise (Ihara et al., 2021; Mayer et al., 2019).

It is possible that while learning to write, the physical production of letters by hand may itself, facilitate the process of learning to write. Also, the automaticity with which adults and older children can locate letters on a keyboard due to letter knowledge and familiarity with a keyboard, is something still to be accomplished by the novice learner. This additional cognitive load for a young learner could be as much or more than learning to form letters by hand.

For children beyond preschool, in addition to depressing the correct letters to type words, they must learn to format sentences, paragraphs and additional characters, such as punctuation. They must also know where and when to locate the shift keys for upper case letters and other keyboard functions such as highlighting, cutting and pasting, paragraph alignment, spacing and layout, printing and how to share the work produced for others to read. Learning to navigate the various software packages can be time consuming and involve skills beyond the reasonable expectations of young children. With regard to spelling, an electronic machine may offer the advantage of spellchecking but if students struggle with spelling, then they may not know which of the alternative spellings on offer to choose. There is also the operation of the computer mouse or mouse pad to consider, an additional skill to be mastered.

Whilst for adults, writing by keying in text might be quick and simple, once they have mastered the skill of typing; it cannot foster the process of learning to write for children in the way that handwriting allows the brain to integrate the physical formation of the letter, with the holding of the visual representation in the brain and the simultaneous auditory representation. As pointed out in the report from the University of Stavanger (2011), beginner writers may be unfamiliar with a keyboard layout and may be learning alphabetic order, which may cause confusion. With these considerations, the suitability of a keyboard as a medium for children to learn literacy skills is questionable.

Advantages of Writing by Hand

The main difference between handwriting and making keystrokes is that of hand movement. It seems therefore that the role of the movements involved in handwriting may be key to determining its superiority as a learning mechanism over using a keyboard. It is well known that physical activity aids learning. Petrigna et al., in their study in 2022, found that physical interventions showed improvements in academic outcomes. It is eminently possible that the movements involved in handwriting therefore contribute more to learning than keyboarding. Each letter takes a different form and producing these by hand requires a unique art form for each letter, which needs to become automatic and fluent. Each unique hand movement helps to embed the shape of the letter in the writer’s mind (University of Stavanger, 2011). The hand movements also activate visual representations thus helping the learner to recall (Longcamp et al., 2005) and reproduce (Labat et al., 2020/21) letters and words.

Kiefer et al., (2015) found that for preschool children, word recall was better for words that were written by hand rather than typed; Longcamp et al, (2008) found the same in adults and Mangen et al, (2015) found the same in adults plus cognitive benefits. Kiefer et al., (2015) proposed that the perception of the letters and the action of writing offered a meaningful coupling which offered superior ability for recall than typing.

Multisensory learning theory (Cleland and Clark, 1966) suggests that individuals learn more easily when several senses are stimulated in parallel. Writing by hand activates sensorimotor and memory areas of the brain (Askvik et al., 2020). Therefore, adding the physical skills involved in letter formation to the language, visual and cognitive skills required to produce handwritten output, should support the learning process. Writing on paper rather than typing leads to greater brain activity and improved memory, which is likely due to the conflation of the varied information associated with writing by hand (Umejima et al., 2021).

As children write by hand, their muscle memory is invoked, reinforcing learning each time they form a letter or word. Children are required to think about the sounds in words (phonological awareness) as they write. The language sounds link to a visual and physical pattern when writing by hand, this would not be the case for keying words into a machine.

There is also something rewarding about physically forming a letter, which is not present whilst keying in words. Ihara et al. (2021) confirmed both these latter points in their comparison of learning by handwriting by inkpen, digital pen and typing. Their results showed that movements involved in handwriting by both ink pen and digital pen, allowed for greater memorisation of new words. They also found that ‘positive mood during learning was significantly higher during handwriting than during typing’.

Labat et al., (2020/1) suggested that sensorimotor experience facilitates the enriched encoding of letters which activates cognitive states of associated prior experiences and subsequent recall. Seeing the letters, hearing the sounds, forming the words, feeling the pen on paper, moving the pen to form the letters and the associated thoughts in the brain create more brain activity than when typewriting and in addition to memory, also help to engender an ideal learning state. The complexity of the task of writing itself stimulates the brain. There is evidence too that handwriting produces faster learning than nonmotor practise (Spilling et al., 2022 and Wiley and Rapp, 2021). Increasing brain activity increases the ability to learn as more synapses (connections between brain cells) are utilised. A young child’s brain has more synapses than an adult which are gradually eliminated through the process of synaptic pruning as synapses remain unused; the early years are thus, the most propitious for the embedding of vital foundational skills.

For teaching young children to write, the finding that writing by hand leads to better letter recognition than learning by using a keyboard, is evidenced by research (Roessingh, 2018; Mayer et al., 2019; Labat et al., 2020/21 and Longcamp et al., 2005), suggesting that handwriting is the best way to begin teaching children about letters.

The ability to handwrite offers the option to handwrite, whether this choice is made or not and the ability to sign a unique signature. Each person has their unique handwriting style which, according to graphology (handwriting analysis) can reflect personality, mood, confidence and even health. This is not the case for typed alphabetic letters (although varying fonts can be chosen). It is possible to recognise a person’s handwriting. A person’s signature is an important identifier and validator of identity on passports and other legal documentation. For this reason alone, it is important to be able to write by hand.

Further evidence for supporting the use of handwriting over keyboarding is that handwriting activates reading circuitry and may thus facilitate reading acquisition (James and Engelhardt, 2012). This further supports the concept of reading and writing as being inextricably interwoven and that of Ehri (1997) that reading and writing is a two-way process. Roessingh (2018) also suggested that printing by hand plays an important role in reading development and that this physical action creates memory traces (changes in the nervous system, brought about by learning) in the brain that assist with the recognition of letter shapes. This also helps to move information from short to long-term memory, which using a keyboard does not. Once handwriting is fluent, short-term memory is freed up, allowing the writer to engage with more complex text. Taking notes by hand has also been found to be superior to note-taking onto a laptop by Mueller and Oppenheimer (2014), who found that the handwriting students were better at answering questions about what they had written.

Another advantage of the physical movement required for handwriting may be that it can be used to focus the mind. The twiddling of a pen may serve a similar purpose to a stress ball. The use of a stress ball distracts a person from what is causing anxiety and helps them to focus on the task literally ‘in hand’. Using a stress ball as a method of distraction was found to work in hospital patients by Kasar et al. (2020). It is known that writing can reduce anxiety for some people and writing is sometimes used as therapy. Handwriting can enable expressive ideas to be explored by physical movement. Research by Mueller and Oppenheimer (2014) showed that as the hand is forming letters, the brain has time to think, possibly creating greater opportunity for creativity and self-expression. This thought processing can involve pathways that manage emotions (Berninger et al., 2009). Writing is a reflection of speaking; it entwines the mind and body. As writing is the transcription of spoken language, the act of writing is sure to evoke emotions associated with the content of the script.

As a letter is handwritten, the body is involved in the process and as such the mind and body work together to produce the letter. The process becomes automatic due to the embodiment of the knowledge of the shape. The writer not only learns how the shape looks but learns the feel of the shape through employment of their motor skills to manifest the shape onto paper. The mind is influenced by the body in the same way as the body is influenced by the mind. In psychology this is termed ‘embodied cognition’.

Recognition of the benefits of handwriting are now seeing the advent of digital handwriting apps which can transform handwriting input via a digital pen to typewritten format. Such pens are more difficult to control (Mayer et al., 2019) and it is very difficult to write neatly with them, but they may well allow children who prefer technology to tradition to practise letter outlines and could facilitate this process, albeit slowly.

It would seem that the benefits of handwriting upon the brain and subsequent learning, far outweigh the perceived benefits of typewriting at speed, as the use of a keyboard is lacking in the summoning of necessary motor and cognitive processes which support letter and word learning.

Conclusion

For most adults, writing skills have become automatic and they need only concern themselves with the content of writing. Producing written work by keyboard can provide a quicker and more efficient method of production for many, once they have sufficient keyboard skills and are well acquainted with their software; although it may not foster creativity in the way that pen and paper can. However, for children who are learning to write, the physical process involved in handwriting has been found to facilitate letter identification and to boost memory recall more than keyboarding and improves the ability to read. It is superior as a learning medium to keyboarding, as the physical activity involved, forces a wider array of areas in the brain to interact in order to effect performance. Depriving a body of this practice could subsequently impact other areas of learning.

For older children, in addition to memory recall, writing by hand can help to generate ideas, organise thoughts, encode ideas and foster creativity; it can also support focus and energy, all necessary skills identified by Levine (2003) as required to produce a piece of writing.

Whilst it can be seen that technology can both support and inhibit the process of learning to write by hand, handwriting itself supports the process of learning to read and therefore has value in the literacy field. It also offers users a skill for notetaking, a means of confirming personal identify, and a creative outlet; it is a requirement for some in the workplace and to date, a method for information gathering and of work production for assessment in schools. It is hard to imagine a world where people are unable to write and it would seem a retrograde step to move in such a direction. If suggestions as elucidated here, of the dwindling of this basic skill are accurate, then it behoves educators to ensure that all children get a sound foundation in the skill of producing handwritten text, as an important precursor to technology-produced text, before this skill is relegated to the annals of time.

References

Askvik, E. O., van der Weel, F. R. and van der Meer, A. (2020). The Importance of Cursive Handwriting Over Typewriting for Learning in the Classroom: A High-Density EEG Study of 12-Year-Old Children and Young Adults. Front. Psychol. 11. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01810

Barus K. H. B. B and Panjaitan N. B. (2022). The Correlation Between Vocabulary Mastery and Writing Skill a Meta-Analysis. Channing: English Language Education and Literature. 7(1), 13-20.

DOI: 10.30599/channing.v7i1.1482

Berninger, V.W., Abbott, R. D., Augsburger, A. and Garcia, N. (2009). Comparison of Pen and Keyboard Transcription Modes in Children with and without Learning Disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly. 32(3), 123-141.

DOI: 10.2307/27740364

Connelly, V., Gee, D., and Walsh, E. (2007). A comparison of keyboarded and handwritten compositions and the relationship with transcription speed. British Journal of Educational Psychology. 77(2), 479-492. DOI: 10.1348/000709906X116768

Conway, P. F. and Amberson, J. (2004). Laptops initiative for students with dyslexia or other reading and writing difficulties: Evaluation report of early implementation, 2002-2003. DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.1.1618.0885

Coombe, G., for Ofqual. (2020). Online and on-screen assessment in high stakes, sessional qualifications. Crown Copyright. Ref: Ofqual/20/6723/1

Cowie, R., Cowie-Douglas, E. and Wichmann, A. (2002). Prosodic characteristics of skilled reading: Fluency and expressiveness in 8-10 year old reader. Language and Speech. 45, 47-82. DOI: 1177/00238309020450010301

Chomsky, C. (1971). Write First, Read Later. Childhood Education. 47(6), 296-300. DOI: 10.1080/00094056.1971.10727281

Cleland, C. C. and Clark, C. M. (1966). Sensory deprivation and aberrant behavior among idiots. American Journal of Mental Deficiency, 71(2), 213-225. PMID: 5338839

Department for Education. (2019). National statistics; national curriculum assessments at key stage 2 in England (interim) Retrieved May 10, 2023 from https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/national-curriculum-assessments-key-stage-2-2019-interim/national-curriculum-assessments-at-key-stage-2-in-england-2019-interim

Dhakal, V., Feit, A. M., Kristensson, P. O. and Oulasvirta, A. (2018). Observations on Typing from 136 Million Keystrokes. In Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. CHI 2018.

DOI: 10.1145/3173574.3174220

Dunst, C. J. and Gorman, E. (2009). Development of Infant and Toddler Mark Making and Scribbling. Center for Early Literacy Learning. 2(2), 1-16.

Ehri, L. C. (1997). Learning to read and learning to spell are one and the same, almost. In Perfetti, C. A., Rieben, L. and Fayol, M. (Eds). Learning to spell: Research, theory and practice across languages (pp. 237-269). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Ehri, L. C. (2000). Learning to Read and Learning to Spell: Two sides of a coin. Topics in Language Disorders. 20(3), 19-36. DOI: 10.1097/00011363-200020030-00005

Ehri, L. C. (2014). Orthographic mapping in the acquisition of sight word reading, spelling memory, and vocabulary learning. Sci. Stud. Read. 18(1), 5–21. DOI: 10.1080/10888438.2013.819356

Friedrich, N., Portier, C. and Stagg Peterson, S. (2021). Investigating the transition from the personal signs of drawing to the social signs of writing. International Journal of Early Years Education. 29(1), 56-74. DOI: 10.1080/09669760.2020.1778450

Ihara, A. S., Nakajima, K., Kake, A., Ishimaru, K., Osugi, K. and Naruse, Y. (2021). Advantage of Handwriting Over Typing on Learning Words: Evidence from an N400 Event-Related Potential Index. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 15, 679191. DOI: 10.3389/fnhum.2021.679191

James, K. H. and Engelhardt, L. (2012). The effects of handwriting experience on functional brain development in pre-literate children. Trends Neurosc Educ. 1(1), 32-42. DOI: 10.1016/j.tine.2012.08.001

Kasar, K. S., Erzincanli, S and Akbas, N. T. (2020). The effect of a stress ball on stress, vital signs and patient comfort in hemodialysis patients: A randomized controlled trial. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice. 41(6), 101243. DOI: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2020.101243

Kay, M. (2016). Literacy through Music. TACTYC. Retrieved May 10, 2023, from https://tactyc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Maria-Kay-Reflections-article.docx

Kim, Y. S. G. (2022). Co-Occurrence of Reading and Writing Difficulties: The Application of the Interactive Dynamic Literacy Model. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 55(6), 447-464 DOI: 10.1177/00222194211060868

Kiefer, M., Schuler, S., Mayer, C., Trumpp, N. M., Hille, K. and Sachse, S. (2015). Handwriting or typewriting? The influence of pen- or keyboard-based writing training on reading and writing performance in preschool children. Adv. Cogn. Psychol. 11(4), 136-146. DOI: 10.5709/acp-0178-7

Kilpatrick, D. A. (2016). Equipped for Reading Success: A Comprehensive, Step-By-Step Program for Developing Phoneme Awareness and Fluent Word Recognition. Casey & Kirsch Publishers:NY

Labat H., Écalle J. and Magnan A. (2021/1). Embodied Cognition and Education: How Does the Sensorimotor Experience Stimulate the Learning of Reading-Writing? In Versace Rémy (Eds). Memory and Cognition: How is the Meaning of the World Constructed Through our Interactions with the Environment? Intellectica, 74, 253-270

Levine, M. (2003). The Myth of Laziness. Simon and Schuster. New York.

Longcamp, M., Zerbato-Poudou, M. and Velay, J. (2005). The Influence of Writing Practice on Letter Recognition in Preschool Children: A comparison between Handwriting and Typing. Acta Psychologica 119(1), 67-79.

DOI: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2004.10.019

Longcamp, M., Boucard, C., Gilhodes, J. C., Anton, J. L., Roth, M., Nazarian, B. and Velay, J. L. (2008). Learning through hand- or typewriting influences visual recognition of new graphic shapes: behavioral and functional imaging evidence. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 20(5), 802-815. DOI: 10.1162/jocn.2008.20504

Mangen, A., Anda, L. G., Oxborough, G. H. and Brřnnick, K. (2015). Handwriting versus Keyboard Writing: Effect on Word Recall. Journal of Writing Research. 7(2), 227-247. DOI: 10.17239/jowr-2015.07.02.1

Mayer C., Wallner S., Budde-Spengler N., Braunert S., Arndt P A. and Kiefer M. (2019). Literacy Training of Kindergarten Children With Pencil, Keyboard or Tablet Stylus: The Influence of the Writing Tool on Reading and Writing Performance at Letter and Word Level. Front. Psychol. 10, 3054. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.03054

Medwell, J. and Wray, D. (2017). What’s the Use of Handwriting?: A White Paper. Retrieved May 10, 2023, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319537899_What's_the_use_of_handwriting_a_white_paper

Moran, R. and Billen, M. (2014). The Reading and Writing Connection: Merging Two Reciprocal Content Areas. Georgia Educational Researcher. 11(1)8.

DOI: 10.20429/ger.2014.110108

Mueller, P. A., and Oppenheimer, D. M. (2014). The Pen Is Mightier Than the Keyboard: Advantages of Longhand Over Laptop Note Taking. Psychological Science, 25(6), 1159–1168. DOI: 10.1177/0956797614524581

The Nation’s Report Card. (2020). How did U.S. students perform on the most recent assessments? Retrieved May 20, 2023, from https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/

Petrigna, L., Thomas, E., Brusa J., Rizzo, F., Scardina, A., Gallassi, C., Lo Verde, D., Caramazza G. and Ballafiore M. (2022). Does Learning Through Movement Improve Academic Performance in Primary Schoolchildren? A Systematic Review. Front. Pediatr. 10. DOI: 10.3389/fped.2022.841582

Puranik, C. S., & Lonigan, C. J. (2012). Early Writing Deficits in Preschoolers With Oral Language Difficulties. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 45(2), 179–190. DOI: 10.1177/0022219411423423

Roessingh H. (2018). Unmasking the Early Language and Literacy Needs of ELLs: What K-3 Practitioners Need to Know and Do. BC TEAL Journal. 3(1), 22-36. DOI: 10.14288/BCTJ.V311.276

Samuel, J. (2023). Writing’s on the wall for the humble pen and pencil. The Times. 27 March. Retrieved May 20, 2023, from https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/writings-on-the-wall-for-the-humble-pen-and-pencil-ctdzsfkpk

Spilling, E. F., Rønneberg, V., Rogne, W. M., Roeser, J. and Torrance, M. (2022). Handwriting versus keyboarding: Does writing modality affect quality of narratives written by beginner writers? Reading and Writing. 35, 129-153. DOI: 10.1007/s11145-021-10169-y

Trubek, A. (2016). The History and Uncertain Future of Handwriting. Bloomsbury Publishing. USA.

Umejima, K., Ibaraki, T., Yamazaki, T. and Sakai, K. L. (2021). Paper Notebooks vs. Mobile Devices: Brain Activation Differences During Memory Retrieval. Frontiers in Behavioural Neuroscience. 15. DOI: 10.3389/fnbeh.2021.634158

The University of Stavanger. (2011). “Better learning through handwriting”. ScienceDaily. Retrieved May 10, 2023, from https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/01/110119095458.htm

Wiley, R. W. and Rapp, B. (2021). The Effects of Handwriting Experience on Literacy Learning. Psychological Science. 32(7), 1086-1103.

DOI: 10.1177/0956797621993111