USING MUSIC TO PROMOTE FOUNDATIONAL LITERACY COMPETENCIES

Dr Maria Kay

a.maria.kay@btinternet.com

ORCID 0009-0001-6445-0647

Abstract

Research into the process of becoming literate mainly focusses on the teaching of the alphabetic principle as a starting point upon school entry. There is, however, a plethora of skills, knowledge and experiences that children bring to literacy learning which underpin and are indicative of literacy success.

Musical activities can offer an ideal vehicle through which these pre-requisites can be promoted. Whilst a wealth of research evidence indicates correlation between musical experience and specific literacy competencies, there is no causal evidence that music promotes literacy learning, as teaching music does not teach literacy. It has been suggested that integrating music and literacy learning could favourably impact literacy skill acquisition.

Using a micro-ethnographic, qualitative design this study sought to examine how a daily literacy-through-music program of 30-40 minutes’ duration, could be devised and implemented in an area of social deprivation over a six-week period, for a group of nine participants aged 3-5 years of age, and the extent to which it could be successful in promoting the identified foundational literacy competencies.

The findings not only demonstrated that such a program could facilitate the acquisition of these competencies, but highlighted differences between a music program and an integrated literacy-through-music program. It also enabled the underlying mechanisms which support literacy learning through a literacy-through-music program to be elucidated. These findings have unique implications for the pedagogical practice of early years practitioners in the establishing of secure literacy foundations for further formal literacy learning.

Keywords: literacy, music, literacy-through-music, foundational literacy, early years

Declarations

No funding was for received for the conduction of this study and there are no conflicts of interest or financial interests.

The research was conducted in accordance with SERA (2005) guidelines.

Informed consent of parents/guardians of the participants was obtained for their participation in the study.

Introduction

Literacy, the ability to understand and use spoken language and to read and write at a level which enables a person to engage fully in the functions of daily life, is vital in today’s world. It is necessary for success throughout school and in the workplace. Whilst preferred teaching methods for reading have changed over decades, from ‘phonics’ in the 1950s, through ‘whole language’, ‘balanced literacy’ and back to ‘phonics’ again today, in search of a panacea for literacy success, not all children learn to read and write easily. Literacy models such as those of Scarborough’s Reading Rope (2001) and the Simple View of Reading - ‘Word Recognition x language Comprehension = Reading Comprehension,’ proposed by Gough and Tunmer (1986), and extended by Duke and Cartwright (2021), serve to guide reading instruction. There is little to guide early years’ practitioners in the laying of foundations for literacy. There is also a gap in qualitative research in the area of literacy, as a pervasive feeling exists that it is in some way epistemologically less reliable to the logic and numerical base of quantitative studies, a point discussed by Dillon (2005) and reiterated by Mirhosseini (2017) who stated that qualitative research continues to be of lower visibility in the area of language and of literacy education. These gaps are addressed in this research.

The period prior to school entry has been described by Dehaene (2009) as a preparatory stage. The emergent literacy stage identified by Rohde, (2015) suggests that there should be no demarcation between the informal preschool literacy learning and that upon school entry, but the reality is that the demarcation is clearly marked by age and not stage. The age at which children enter formal schooling varies across Europe and the USA, from the age of four years in England to the age of seven years in Finland. A later start offers greater opportunity for children to gain experience, knowledge and skills which will underpin future proficiency in reading and writing.

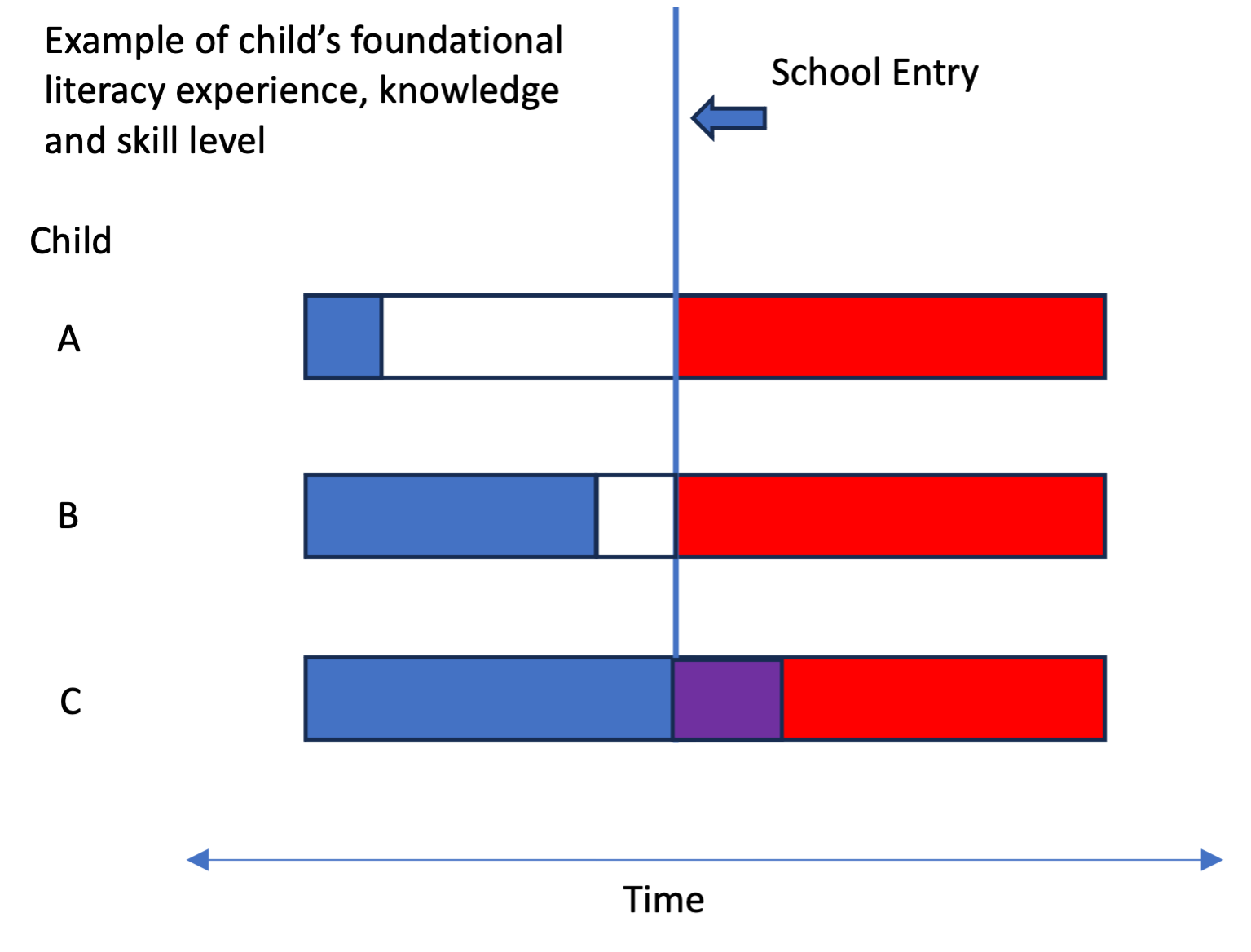

Figure 1. below illustrates how gaps in early learning will affect literacy progress upon school entry. Child C has passed the emergent literacy stage and is beginning to read and write and Child B has many competencies which will support him upon school entry and with a little extra help he may become competent. Child A however, is lacking the multifarious knowledge, skills and literacy experiences which will ensure literacy success. Such a gap for some children can be a chasm and is known to persist in what is referred to as ‘The Matthew Effect’ in education where children with a poor start do not catch up.

Figure 1.

Children’s possible array of foundational literacy experience, knowledge and skills upon school entry

Blue = Foundational literacy experience, knowledge and skills

Red = The teaching of formal literacy skills – phonics

Purple = The teaching of formal literacy skills to a child who already has some of these skills

White = Foundational literacy experience, knowledge and skills gap

The home learning environment can be a rich source of foundational literacy learning for children (Zhakim, 2021). It is judicious therefore, to consider children’s early literacy experiences. All children do not benefit from the same ‘literacy-rich’ and life experiences as would be propitious. Corriveau et al, (2010) found that children who entered school with little pre-reading skills, phonological awareness and poor receptive vocabulary, were at a disadvantage.

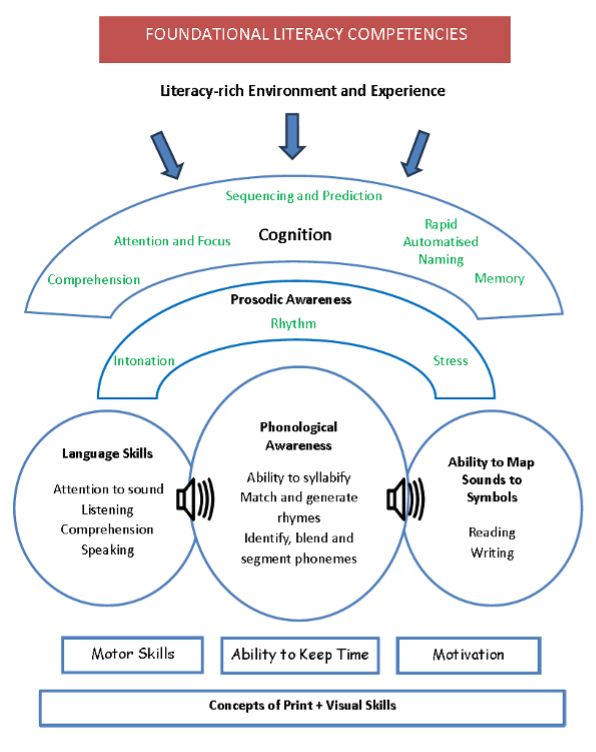

Figure 2.

Foundational Literacy Competencies

When children enter pre-school provision, there is often little understanding of what children require in order to facilitate literacy success (Rohde, 2015) and practitioners may often believe that teaching letters is the starting point. As can be seen from Figure 2., there is a multifarious set of competencies which support success in literacy learning and which are in place prior to formal literacy learning for those who appear to easily master what is required.

A literature review revealed the experiences, skills and knowledge upon which literacy success is dependent and these are identified in Figure 2. Children with prior exposure to literacy experiences will assimilate bibliographic knowledge and learn the concepts of print prior to school entry, but this cannot be assumed for all children.

Children benefit from the cognitive skills of comprehension (Stothard and Hulme, 1992), ability to focus and pay attention (Dice and Schwanenflugel, 2012), the ability to sequence and predict what is to follow (Stein, 2022) and auditory and visual memory. Random automatised naming is also predictive of reading ability (McWeeny et al., 2022).

Written language is predicated upon spoken language, therefore, facility with spoken language is imperative to literacy. Roulstone et al., (2011) determined that language development at the age of two years predicts future literacy performance. Paucity of language skills presents a barrier to literacy.

In order to comprehend language, an awareness of prosody is required, to not only interpret the words being spoken but to infer meaning from the way in which they are spoken. Prosody is a term referring to the linguistic functions of speech such as intonation, rhythm and stress. It describes ‘how’ we speak. Consider for example, the sentence, ‘He didn’t ride to the park.’ By emphasising the word, ‘he’, ‘ride’ or ‘park’ it is possible to change the inference of the statement. By altering the rhythm, stress and intonation it is also possible to deliver the sentence as a question.

Phonological awareness (PA) is the undisputed major predictor of literacy success with phonemic awareness being the strongest predictor of the three levels of syllable, rhyme and phoneme (Martin et al., 2024). This awareness of the sound elements of language is what enables children to be able to play with these sounds and ultimately blend and segment them when they are matched to corresponding graphemes. Prior to this, children need an awareness of sound and the ability to tune in to sounds and discriminate between them.

Although visual skills are not sound related, they are incorporated in this study and determined as skills of discrimination, identification of printed items and response to visual stimuli; they are important elements in learning to read and write.

A strong positive relationship exists between motor proficiency and pre-reading skills (Milne et al., 2018). Movement stimulates the brain, thus impacting learning, and gesture supports language learning (Novack and Goldin-Meadow, (2015). Movement helps learning to become embodied. Macrine and Fugate, (2022) advocate for a holistic approach to learning and teaching and assert that embodied learning can support vocabulary acquisition, language development and comprehension, and handwriting. Macrine and Fugate (2021:3) refer to the fact that ‘Our current educational delivery systems and approaches can be traced back to ‘disembodied views’ of human thinking.’ This alludes to the general gap between what is known about how children learn - that they should be moving, and the observation of classroom practice, where they are often observed to be sitting.

Furthermore, the ability to keep time by entrainment to a beat, encourages fluency of auditory-motor timing, a skill required for reading and writing fluency (Tierney and Kraus, 2014). Fiveash et al. (2023) avered that rhythm development is experience dependent, and also suggested that rhythmic engagement through music is rewarding. The rewarding nature of moving to music is a motivational feature, further supporting the argument for the use of music as an ideal learning medium.

Music and Literacy

The use of music in education is much undervalued (Collins et al., 2020), yet it is acknowledged that the benefits of participation in musical activities are far-reaching – brain stimulation (Schlaug et al., 1995), benefits to speech processing (Patel, 2014), assistance with memory recall (Parbery-Clark et al., 2009), music is motoric (Toyka and Freund, 2007), enhanced detection of ‘speech-in-noise’ (Slater et al., 2015), music supports the ability to entrain to a beat by engaging auditory-motor systems (Corriveau and Goswami, 2009; Slater at al., 2013) and Tierney and Kraus (2013a:228) stated that ‘one of the reasons musical training can be such a powerful educational tool is that music is inherently rewarding, emotion-inducing and attention grabbing.’

There is a wealth of literature attesting to the correlation between various musical experiences (formal instrumental lessons, singing, listening to music, informal musical experiences) and various literacy outcomes (language, PA, RAN, fluency) - Strait, and Kraus, (2011), Slvec, (2012), Tierney and Kraus, (2013a), Bhide et al., (2013 and Frasher, (2014). However, the evidence is correlational; there is no causal evidence because teaching music, does not teach children to read and write. The reason for this correlation may be due to the many areas of commonality between music and language (Pino et al., 2023) and as written language is predicated upon spoken language; this accounts to some degree for the transfer of skills between music and literacy. Explanations for such transfer have been hypothesised - The OPERA hypothesis (Patel, 2011) and the PAT hypothesis, (Tierney and Kraus, 2014). There is however, a causal relationship between informal music activities and auditory discrimination, which was established by Putkinen et al., (2013).

The integration of music and literacy activities to promote literacy outcomes would obviate the need for transfer and some researchers have suggested this (Frasher, 2014; Verney, 2011; Kay, 2013) and called for further research in this area (Rautenberg, 2015). Researchers such as Bolduc and Lefebvre, (2012) and Bostelman, (2008) have suggested that in interventions in which music has been integrated with literacy and used with the intention to promote literacy outcomes, then these have been the most efficacious. The seminal work of Standley and Hughes in 1997, offers one such study and this was replicated by Register in 2001. The results from their study (Standley and Hughes 1997:5) demonstrated that ‘the more focused the music activities were on a specific skill, the more effective they were in teaching print conventions and writing skills as intended.’ This research aimed to focus on the promotion of the identified foundational literacy competencies through a musical program and to identify any underlying mechanisms which could account for any success.

Method

An interpretivist paradigm was adopted to ‘understand the subjective world of human experience’ (Cohen et al., 2011:17) based on ontological assumptions that reality is subjective and the epistemological assumptions that knowledge is gained inductively, arises from particular situations and is gained through personal experience. An interpretive approach relies on predominantly naturalistic methods such as observation which was used in this case.

A qualitative, micro-ethnographic study, as defined by LeBaron, (2012) with analysed video recordings paying attention to participants’ talk, embodied behaviours and their use of tools, in the children’s natural preschool setting, was conducted. The purpose was to examine how literacy competencies could be promoted through musical activities in a purpose-designed, integrated literacy-through-music (LtM) intervention. The ‘embedded-explicit model’ of literacy intervention design from Justice and Kaderavek, (2004) was developed as a preventative framework for conceptualising the delivery of emergent literacy interventions for young children at risk of later reading difficulties and was therefore an ideal model to use for this research.

The research was undertaken in a preschool centre in an area of social deprivation, based upon findings from Sosu and Ellis, (2014) that children in such areas are at risk of low language abilities which impact upon literacy. The nine participants, five male and four female aged between three and five years of age, were randomly selected by the centre head. The study was conducted every day for 30-40 minutes over six weeks, through a range of musical activities.

Data Collection and Analysis

Twenty-two sessions were video-recorded by older children from the adjacent primary school acting as videographers. The sessions were designed and conducted in accordance with SERA ethical guidelines (SERA, 2005). Selected video footage of six sessions was chosen for transcription and deductive coding was used to investigate progress in the competency areas for each participant. The findings showed that all children acquired some literacy outcomes over time. One participant possessed all the knowledge and skills at the beginning of the program which would be expected to assure her future literacy success; it was not possible to assess her previous experience. Strengths and weaknesses were identified for the other participants. This indicated that the program could be used as an assessment tool to identify children’s foundational literacy competencies and areas of need.

Interpretation of the Data

The data that was collected, offered a rich source of information related to children’s literacy skill acquisition through integrated music and literacy activities, enabling a ’Literacy-through-Music’ (LtM) model to be formulated. The data enabled the identification of differences between a musical program for children and a LtM program, in terms of design and delivery and the activities which were most beneficial in promoting foundational literacy outcomes. It showed that children were able to acquire literacy competencies through the integrated activities. It was possible to identify areas of difficulty and to implement immediate supportive strategies where appropriate. Finally, the data revealed possible reasons for skill acquisition which ultimately provided six underlying mechanisms to explain how a LtM program could be successful in promoting foundational literacy competences.

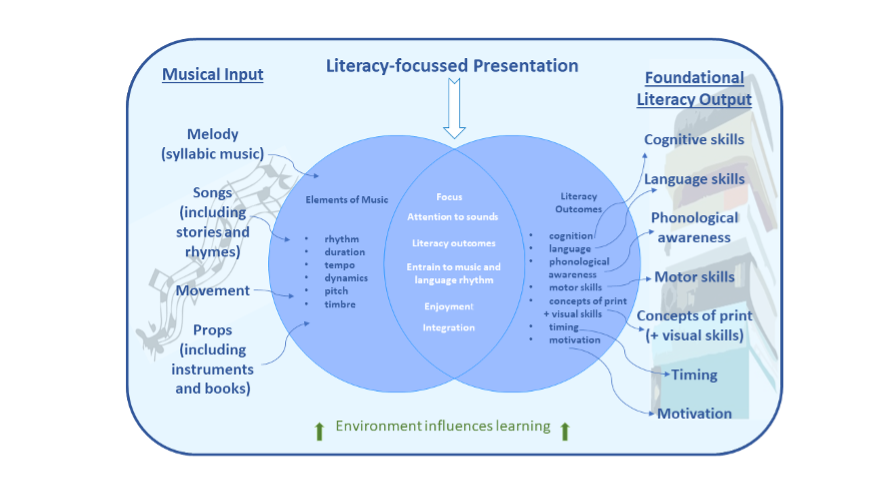

1 A Music Program Versus a LtM Program

Concordant with a musical program, the LtM program in the study was delivered through musical activities, and promoted the musical elements of rhythm, duration, tempo, dynamics, pitch and timbre, as these elements help to attune children’s ears for auditory discrimination. Various props were used to engage the participants and to stimulate imagination. The recorded melodies to accompany the activities had introductory and ending pieces to prepare participants for starts and finishes. In contrast to a musical program, the learning outcomes were literacy competencies as identified in Figure 2 – cognitive skills, language skills, phonological awareness, motor skills, concepts of print and visual skills, the ability to keep time and motivation. Props used included, books, (picture, rhyme and storybooks) to promote response to visual stimuli, to promote language comprehension, to demonstrate the relationship between language and text and to demonstrate the purpose of text. Another feature of the LtM program was that the recorded music was syllabic as opposed to melismatic; each note in the music corresponded to a syllable in the lyrics of the accompanying song. This helped the demarcation of the syllabic components in words as the change in syllable was highlighted by the change in musical pitch. Also contrasting with most musical programs was that the presenter was a literacy specialist.

2 Competencies Acquired

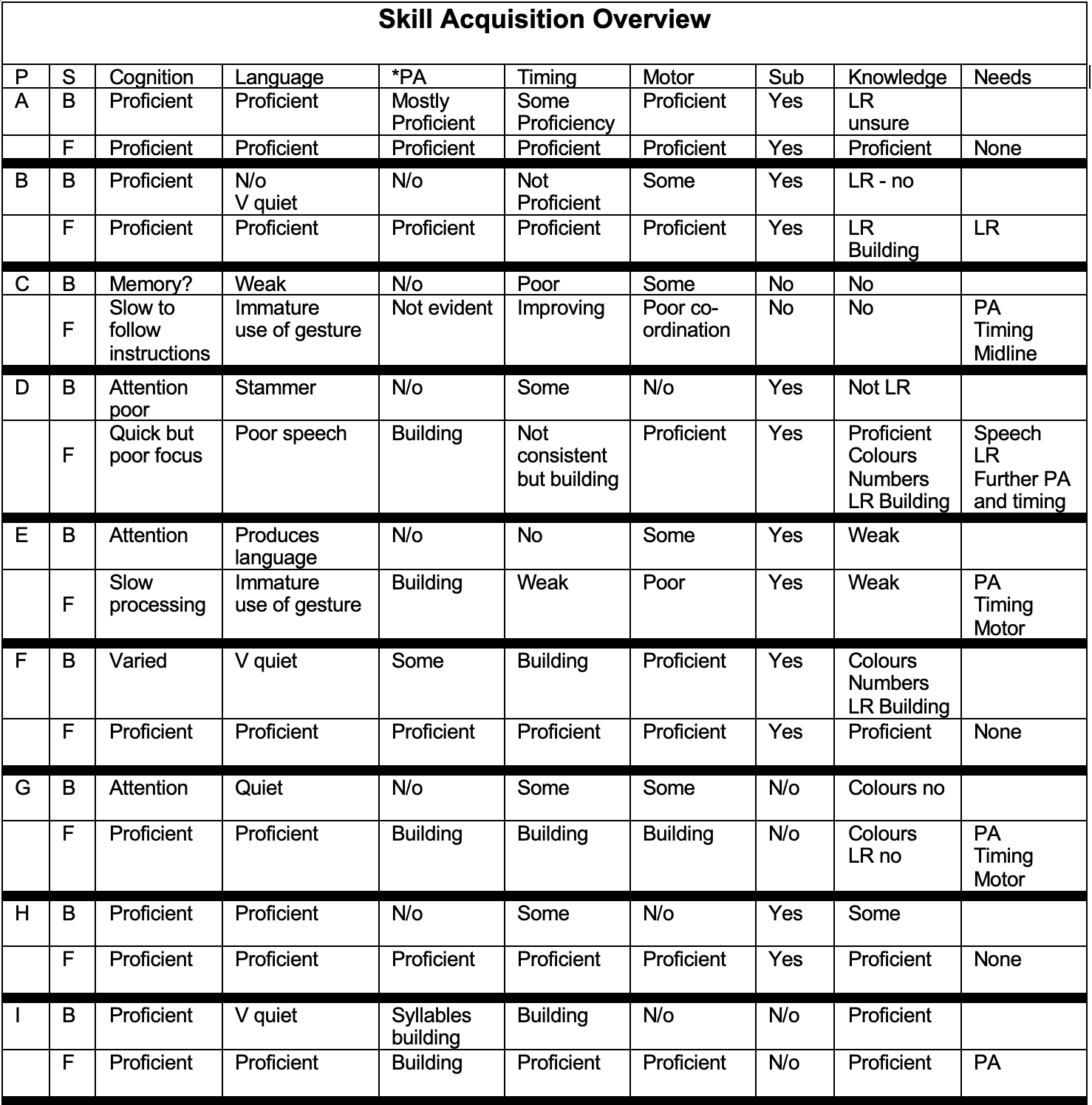

The figure below summarises the possession of skills at the first and last sessions for each participant to allow skill acquisition over time to be compared.

Figure 3.

Skill Acquisition Overview

*P – Participant

*S – Session – B = beginning or F = Final

*PA - Phonological awareness

*Sub – Subconscious body movement in time to music

*LR – Knowledge of left and right

*N/o – Not observed

As might be expected, all participants improved in skill building over time as this was the focus of the intervention. However, not all participants progressed at the same rate and not in the same skill areas. All participants engaged well with the activities. All participants began to learn the lyrics and movements to the activities, demonstrating memory retention and recall. Some were slower than others at predicting what was to come. Comprehension of the storylines was assessed through discussion and the posing of questions. For example, a book, ‘My Cat Ben’ was used and the participants sang the song about a greedy cat, as the music was played, and the pages turned of the book with each verse. Once the participants were familiar with the book, the presenter asked them to speak about what happened in the story, to recall the events in order, to describe the cat and the events, and to share their own experiences of their pets at home. This allowed the researcher to observe the ability of the participants to produce language, to demonstrate their cognitive skills and gauge motivation for the activity. Some participants were able to demonstrate awareness and use of prosody and were observed to use gesture to support their speech. They were all excited by the activity and keen to proffer answers to all questions posed. As can be seen from Figure 3., two thirds of the participants were considered proficient in language at the end of the program; two participants (A and H) were proficient at the beginning. Two participants (C and E) used gesture instead of speech on occasions, one of these spoke frequently, but speech was immature, and the other spoke rarely; these were regarded as signs of immaturity in language development. Participant C was also weak on memory recall. One participant (D) had a stammer, yet a high level of engagement with the activities and frequent contributions.

The presenter ensured promotion of prosodic awareness by appropriate modulation of her voice and encouraging the participants to do the same. Participants were able to enunciate and to tap out the syllables simultaneously, in the word ‘alligator,’ a word from a song in the program. The participants were also asked to choose words of their own choice on a theme, which they became adept at syllabifying. Ability to rhyme was promoted through the singing and reciting of rhymes; the presenter used the strategy of cloze to encourage the interposing of rhyming words, and by drawing attention to the similar ending sound patterns. One participant, of her own volition when the presenter mentioned a rhyme about mice eating cheese said, ‘cheesey wheezy’ to herself. This was not part of the rhyme but showed that she was aware of and able to generate rhymes.

The presenter used an alphabet book with songs, towards the end of the program to further promote phonemic awareness and to demonstrate how sounds corresponded to alphabetic symbols. She ensured that learning was relevant to the children and letters were not presented out of context. The use of a book also helped to promote concepts of print. In Figure 3., where participants were not proficient in all three levels of phonological awareness it was noted that further practise was required.

The ability to subconsciously move the body in time to music was noted in six participants out of nine. The perception of beat is believed to be innate (Winkler et al., 2009) whilst the ability to synchronise to a beat is not, and inability to synchronise to a beat has been linked with poor pre-literacy skills (Carr et al., 2014). All participants showed improvement in ability to keep time over the duration of the program. Similarly, participants showed improvement in motor skills over time.

As general indicators of knowledge relevant to the participants’ ages they were asked to name colours, identify written numbers and identify left and right sides of their bodies consistently. It can be seen from Figure 3., that participants who were weak, tended to have weaknesses across all areas and similarly, those with strengths were across all areas. Areas in which the participants required further practise were identified as ‘Needs’ in the final column.

3 Underlying Mechanisms for the Successful Acquisition of Foundational Literacy Skills

Inductive codes were generated to identify themes which underlaid the acquisition of foundational literacy skills. Some activities were identified as more popular than others as they had higher levels of participation, evoked more positive body language (laughing and smiling) and had the greater number of requests for performance or repetition. These activities were also the ones for which the most skills were demonstrated. Ultimately six possible underlying mechanisms were identified:

- as the activities were engaging, this held the participants’ attention

- through the activities, the presenter drew the participants’ attention to sound and specifically to the sound segments in language

- the presenter ensured that the focus was explicitly upon literacy outcomes

- the activities facilitated the ability of the participants to entrain to a beat (tapping performance is linked to reading attainment (Tierney and Kraus, 2013b) and to discriminate and copy rhythms in both music and language

- participants engaged readily with the activities and demonstrated enjoyment

- and the activities promoted the ability of the participants to integrate their knowledge and skills and apply them to tasks set.

The data collected enabled the formulation of a LtM model (Figure 4.) to explain how musical activities can be integrated with literacy learning to promote foundational literacy outcomes. Initially, activities must be chosen which will be engaging; they must be suitable for the children in terms of relevance of content and ease of participation. Accompanying music should be syllabic with an introductory and ending section. A variety of activities should be presented in terms of locomotion, action songs and ones utilising props, instruments, books and puppets. The use of finger puppets and instruments for example, support the development of fine motor skills and co-ordination which will be required later for writing. Elements of music as indicated can be promoted to draw attention to variation in sounds and specifically in language sounds. Children must be able to focus on the activities and pay attention to variations in sound. The focus must be on literacy outcomes. Children should be encouraged to move in time to the music and language of the songs/rhymes. The activities should be enjoyable and should integrate the competencies required as well as the integration of music with literacy outcomes. The literacy outcomes are repeated as outputs in the model, to reinforce that when these are the focus of the intervention then the output will reflect this. A musical environment is one which is conducive to learning, as it encourages engagement, is inclusive and naturally integrates a wide range of concepts and skills.

Figure 4.

Literacy-through-Music Model

Conclusion

This study makes a unique contribution to research into the integration of music and literacy to support the development of foundational literacy competencies. It was able to address a gap in the literature of qualitative studies in early literacy learning through integrated music and literacy activities, and to show how music can be used to provide an ideal vehicle through which to promote early learning. Rohde (2015) also points to a gap between educational research and educational practice in the awareness of foundational literacy skill provision of early years practitioners, one which this research also aims to address. In contrast to studies undertaken in a laboratory or to show correlation between discrete variables, this study brings research and practice together, as the intervention was conducted as part of a normal day in an early years setting and sought to provide integrated activities and to promote the integration of learning domains.

Children learn best when they are interested (Harackiewicz, et al., 2016), and when the content is enjoyable. This is a point identified as underlying the efficacy of the LtM program devised for this study and a point recognised by the Finnish curriculum, which states that ‘Children have a right to learn through play with joy’ (Finnish National Board of Education, 2010).

The differences between a music program and a LtM program lie predominantly in the focus upon literacy outcomes and the ability of the presenter to draw children’s attention to the sounds in language as well as those in music. Through the activities in the program, the participants were able to play with the sound segments of words, thus developing both language comprehension and production abilities, (including prosodic awareness) and phonological awareness, the main predictors of literacy success (Goswami and Bryant, 1990; National Early Literacy Panel, 2008). Most activities involved motor skills and particularly auditory-motor skills to help participants to entrain to the rhythm in language. All participants improved in this vital area. The activities were motivational and enabled a broad spectrum of skills to be promoted simultaneously.

The plethora of benefits of undertaking musical activities themselves, augmented the value of the program in addition to the wealth of benefits to literacy for example, focus on sounds, rhythmic training, promotion of language comprehension and production, memory retention and recall, locomotion and balance, and phonological awareness. The use of music fostered the integration of many skills – auditory, gross and fine motor, language, cognitive, social, emotional and timing. This integration serves to engage both hemispheres of the brain simultaneously, thereby stimulating neuronal activity and learning capacity. The multi-sensory nature of the experiences also promoted embodied learning in a rich learning environment which was ideally suited to children of this age.

Recommendations

The findings of this study suggest that using integrated music and literacy activities as a vehicle through which to deliver foundational literacy outcomes would be propitious. Kraus, (2019) suggested that two years is the optimum time for musical activities to effectively make changes in the brain, in which case, preschool settings would benefit from implementing a LtM program for children aged three to five years of age.

Limitations

Limitations of the study were the small sample size and duration of the study. A longitudinal study would be able to assess the longer-term benefits of implementation of a LtM program.

REFERENCES

Bhide, A., Power, A. and Goswami, U. (2013). A rhythmic musical intervention for poor readers - A comparison of efficacy with a letter-based Intervention. Musical Intervention for Poor Readers, 7(2), 113-123. https://doi.org/10.1111/mbe.12016

Bolduc, J. and Lefebvre, P. (2012). Using nursery rhymes to foster phonological and musical processing skills in kindergarteners. Creative Education, 3(4), 495-502. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2012.34075

Bostelman, T.J. (2008). The Effects of Rhyme and Music on the Acquisition of early Phonological and Phonemic awareness skills. Thesis, (MA ed), Defiance College, Ohio.

Carr, K. W., White-Schwoch, T., Tierney, A. T., Strait, D. L. and Kraus, N. (2014). Beat synchronization predicts neural speech encoding and reading readiness in preschoolers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 111, 14559-14564. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1406219111

Cohen, L., Manion, L. and Morrison, K. (2011). Research Methods in Education 7th edition, Routledge.

Collins, A., Dwyer, R. and Date, A. (2020). Music education A sound investment. A report commissioned by, Alberts, The Tony Foundation.

Corriveau, K. H., Goswami, U. and Thomson, J. M. (2010). Auditory processing and early literacy skills in preschool and kindergarten population. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 43(4), 369–382. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219410369071

Dehaene, S. (2009). Reading in the Brain: The new science of how we read. Penguin.

Dice, J. L., and Schwanenflugel, P. (2012). A structural model of the effects of preschool attention on kindergarten literacy. Read Writ, 25, 2205-2222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-011-9354-3

Dillon, D. R. (2005). There and Back Again: Qualitative Research in Literacy Education. Reading Research Quarterly, 40(1), 106-110. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4151723

Duke, N. K. and Cartwright, K. B. (2021). The science of reading progresses: Communicating advances beyond the simple view of reading. Reading Research Quarterly 56 (S1), S25-S44. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.411

Finnish National Board of Education (2010). National core curriculum for pre-primary education. https://www.oph.fi/en/statistics-and-publications/publications/new-national-core-curriculum-basic-education-focus-school.

Frasher, K. D. (2014). Music and literacy: Strategies using comprehension connections by Tanny McGregor. General Music Today, 27(3), 6-9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1048371314520968

Goswami, U. and Bryant, P. (1990). Phonological skills and learning to read, Essays in developmental psychology. Psychology Press Ltd.

Gough, P. and Tunmer, W. (1986). Decoding, reading and reading disability. Remedial and Special Education, 7, 6-10. https://doi.org/10.1177/074193258600700104

Harackiewicz, J. M., Smith, J. L. and Priniski, S. J. (2016). Interest matters: The importance of promoting interest in education. Behav. Brain Sci. 3(2), 220-227. https://doi.org/10.1177/2372732216655542

Justice, L. M. and Kaderavek, J. N. (2004). Embedded-explicit emergent literacy intervention I: Background and description of approach. Language, Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 35, 201-211. https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461(2004/020)

Kay, M. (2013). Sound Before Symbol: Developing Literacy through Music. SAGE Publications.

Kraus, N. (2019). Music and the Mind with Dr Nina Kraus. [Video] YouTube. https://youtu.be/43I_PHyb_K8?si=TJe-fVeAosm9kaCl

LeBaron, C. (2012). Microethnograpy. The International Encylopedia of Communication.

https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405186407.wbiecm082.pub

McWeeny, S., Choi, S., Choe, J., LaTourrette, A., Roberts, M. Y. and Norton, E. S. (2022). Rapid automatized naming (RAN) as a kindergarten predictor of future reading in English: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Reading Research Quarterly. 57(4), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.467

Macrine, S. L. and Fugate, J. M. B. (2021). Translating embodied cognition for embodied learning in the classroom. Frontiers in Education, Neuroscience, Learning and Educational Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.712626

Macrine, S. L. and Fugate, M. B. (Eds.). (2022). Movement Matters: How embodied cognition informs teaching and learning. MIT Press.

Martin, J., Bowl, M. and Banks, G. (Eds.). (2024). Mapping the field: 75 Years of educational review, Volume 2. Routledge.

Milne, N., Cacciotti, K., Davies, K. et al. (2018). The relationship between motor proficiency and reading ability in Year 1 children: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr, 18, 294. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-018-1262-0

Mirhosseini, S-A. (Ed.) (2017). Introduction: Qualitative Research in language and Literacy Education in Reflections on Qualitative Research in Language and Literacy Education (pp1-13). Springer.

National Early Literacy Panel (2008). Developing Early Literacy: Report of the National Early Literacy Panel. National Institute for Literacy.

Novack, M. and Goldin-Meadow, S. (2015). Learning from gesture: How our hands change our minds. Educational Psychology Review, 27(3), 405-412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-015-9325-3

Parbery-Clark A., Skoe, E, Lam, C and Kraus, N. (2009). Musician enhancement for speech-in-noise. Ear and Hearing, 30(6),653-1. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181b412e9

Patel. A. D. (2011). Why would musical training benefit the neural encoding of speech? The OPERA hypothesis. Frontiers in Psychology, Hypothesis and Theory Article, 2(142). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00142

Patel, A. D. (2014). Can nonlinguistic musical training change the way the brain processes speech? The expanded OPERA hypothesis. Hear Res. 308, 98-108. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2013.08.011

Pino, M. C., Giancola, M. and D’Amico, S. (2023). The association between music and language in children: A state-of-the-art review. Children, 10(5), 801.

https://doi.org/10.3390/children10050801

Putkinen, V., Tervaniemi, M. and Huotilainen, M. (2013). Informal musical activities are linked to auditory discrimination and attention in 2–3-year-old children- an event-related potential study. European Journal of Neuroscience, 37, 654-661. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejn.12049

Rautenberg, I. (2015). The effects of musical training on the decoding skills of German-speaking primary school children. Journal of Research in Reading. 38(1), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrir.12010

Register, D. (2001). The effects of an early intervention music curriculum on pre-reading/writing. Journal of Music Therapy, 38(3), 239–248. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/38/3/239

Rohde, L. (2015). The comprehensive emergent literacy model: Early literacy in context. SAGE Open, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015577664

Roulstone, S., Law, J., Rush, R., Clegg, J. and Peters, T. (2011). The role of language in children’s early educational outcomes. Research Brief. DFE-RB 134, ISBN 978-1-84775-945-0.

Scarborough, H.S. (2001). Connecting early language and literacy to later reading (dis)abilites: Evidence, Theory, and Practice. In S. Neuman & D. Dickinson (Eds.). Handbook for research in early literacy, 97-110. Guilford Press.

Schlaug, G., Jäncke, L., Huang, Y., Staiger, J. F. and Steinmetz, H. (1995). Increased corpus callosum size in musicians. Neuropsychologica, 33(8), 1047-1055. https://doi.org/10.1016/0028-3932(95)00045-5

SERA (2005). Scottish Educational Research Association Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research. SERA.

Slater, J., Strait, D. L., Skoe, E., O’Connell, S., Thompson, E. and Kraus, N. (2015). Music training improves speech-in-noise perception- Longitudinal evidence from a community-based music program. Behavioural Brain Research, 291, 244-252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2015.05.026

Slater, J., Tierney, A. and Kraus, N. (2013). At-risk elementary school children with one year of classroom music instruction are better at keeping a beat. PLoS ONE, 8(10), e77250. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0077250

Slvec, L. R. (2012). Language and music: sound, structure and meaning. WIREs Cogn. Sci., 3, 483-492. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcs.1186

Sosu, E. and Ellis, S. (2014). Closing the Attainment Gap in Scottish Education. Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Standley, J. M. and Hughes, J. E. (1997). Evaluation of an early intervention music curriculum for enhancing pre-reading/writing skills. Music Therapy Perspectives, 15, 79-85. https://doi.org/10.1093/mtp/15.2.79

Stein, J. (2022). The visual basis of reading and reading difficulties. Front. Neurosci. 16, 1004027. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2022.1004027

Stothard, S. E. and Hulme, C. (1992). Reading comprehension difficulties in children. The role of language comprehension and working memory skills. Reading and Writing, 4, 245-256. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01027150

Strait, D. and Kraus, N. (2011). Can you hear me now? Musical training shapes functional brain networks for selective auditory attention and hearing speech noise. Frontiers in Psychology, 2(113). https://doi.org/10.2289/fpsyg.2011.00113

Tierney, A. and Kraus, N. (2013a). Music Training for the Development of reading skills. In: M. Merzenich, M. Nahum and T. Van Vleet, (Eds.). Progress in Brain Research, 209-241. Academic Press.

Tierney, A. T. and Kraus, N. (2013b). The ability to tap to a beat relates to cognitive, linguistic and perceptual skills. Brain and Language, 124, 225-231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandl.2012.12.014

Tierney, A. T. and Kraus, N. (2014). Auditory-motor entrainment and phonological skills: precise auditory timing hypothesis (PATH). Front. Hum. Neurosci. 8, 949. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00949

Toyka, K. V., and Freund, H. J. (2007). Music, motor control and the brain. Brain, 129(10), 2794-2798. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awl231

Verney, J. P. (2011). Rhythmic perception and entrainment in 5-year-¬old children - An exploration of the relationship between temporal accuracy at four isochronous rates and its impact on phonological awareness and reading development. Thesis, (Dr Phil), The Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge.

Winkler, I., Haden, G., Ladinig, O., Sziller, I. and Honing, H. (2009). Newborn Infants Detect the beat in music. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106(7), 2468-2471. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0809035106

Zhakim, A. (2021). Pre-school children’s learning and development of literacy in the home learning environment in Kazakh families. (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Aberdeen, Scotland, UK.